.

On the night of June 23rd that year, the only lamp still lit in the university residence was mine. From the third floor, I could take in the sky ablaze above the city and the festivities. In Porto, it’s mandatory to enjoy oneself on the eve of St. John’s Day. Patios, stairways, alleys, passageways, squares, and avenues fill with noise, colored paper streamers, and the glint of sardine scales. It is compulsory to go out, to mingle, to raise a racket, to drink with abandon, to brandish leeks and press them against the insincerely naïve noses of young women. Tradition has it that this is the solstice night. Even if it’s not the shortest night of the year, it is certainly the longest. Every reveler knows that.

As for me, I stubbornly shut myself in to study Linguistics. From outside, the world burst in—loud, full of life—like a stab to the heart. Through the windowpane I could see the rooftops and church towers where the trailing fire of paper lanterns climbed skyward, the scattered light from crowded balconies, from grills and barbecues burning bright, and the lagging groups running about with their plastic hammers. I could swear the dozens of students’ rooms were empty. Since mid-afternoon, I hadn’t seen a soul in the hallways, nor heard a single voice inside the building.

Martinet’s notes struck me as monstrously tedious. I underlined them with a fluorescent marker and recited the glosses aloud from my notebook. I was alone.

It was in that solitude that I noticed the sky sinking into ever darker shades of green-black, eerily like chromium oxide, suffocating the horizon. The first lightning bolt and thunderclap I mistook for part of the celebration. But then came more. The storm wasted no time shaking the windows and unleashing the most vengeful rain I had ever witnessed.

In an instant, cries of confusion multiplied—hysterical, terrified. Sheets of rain hammered mercilessly against the long tables on the terraces. The grills were dragged under awnings however best they could. Old and young alike huddled together in kiosks and under doorways. The scene of the commotion struck me as so amusing, so full of warmth, that I opened a drawer and took out my Leica.

Despite the fogged glass and saturated air, the landscape had changed. It seemed beautiful now—human, sheltering, inviting.

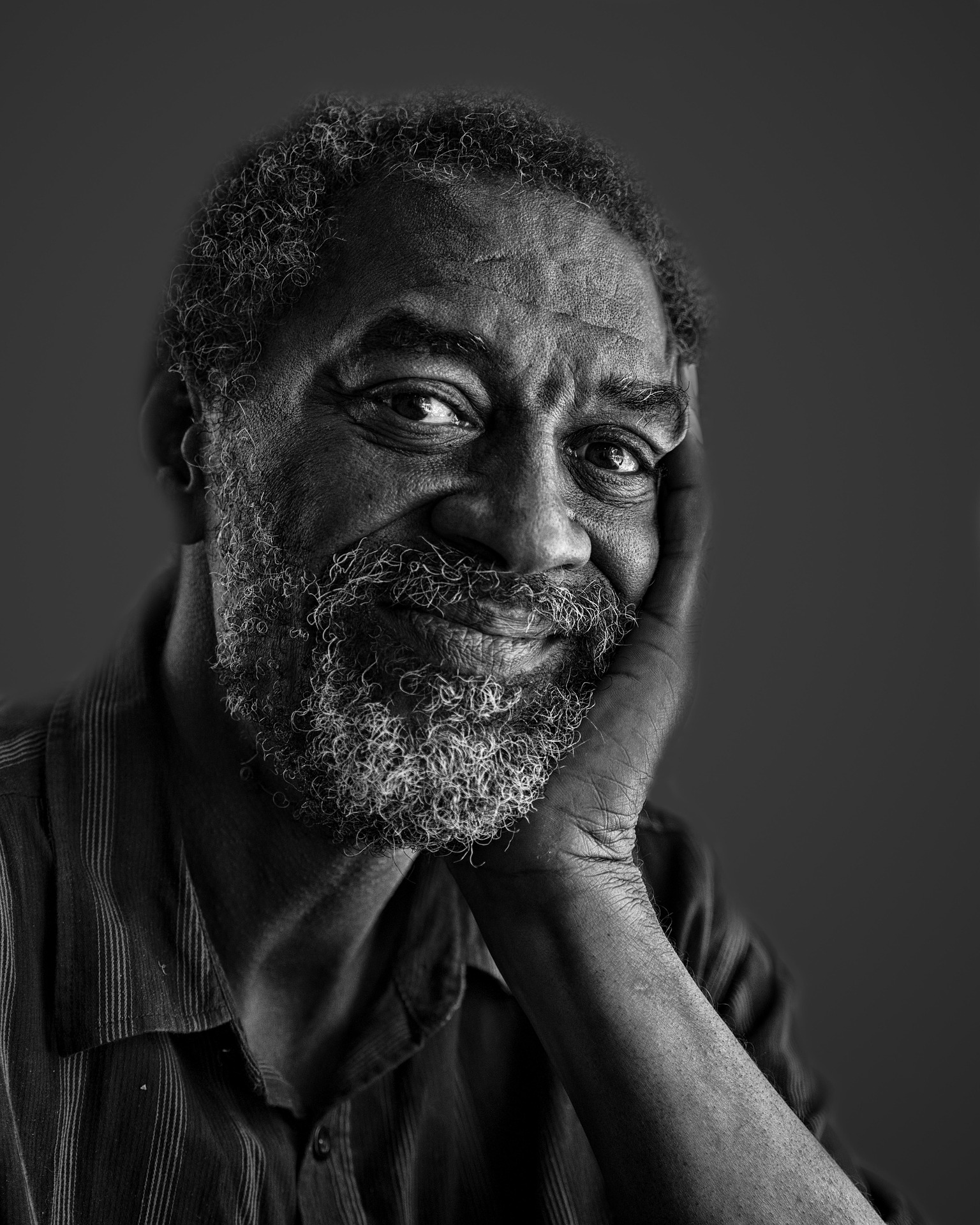

Far away, the floodlights of the churches lit the storm. Closer, the streetlights revealed the damage. I went down to see it better. As soon as I opened the door, I came face to face with one of those poor souls so common in our cities.

— Didn’t mean to scare you, son. Forgive me!

— You didn’t. Don’t worry!

I hesitated for a moment, unsure whether to step out or invite him in. There was a mix of smoke and vapor rising from the asphalt. My camera was ready.

— This rain. Who could have guessed!

The man said nothing. He only shrugged. In one hand he held an apple, in the other a nylon sack. That downpour, it seemed, was nothing unusual to him.

— You’ll be soaked through… Come in, take shelter!

Without a word, the man obeyed.

I looked at the street: a box of peppers on the ground, abandoned beers, cats under cars, smoke. St. John, it seemed, had proven himself indecent. I couldn’t bring myself to fire the flash. Then the man said:

— In any case, what you’re feeling now is déjà vu.

And it was true: the whole scene felt familiar, as if some link in my memory had sparked the impression I had lived that moment before. The man—though I’d never seen him—was, I could swear, oddly familiar.

— You’re not going to take a single shot with that camera. The objects don’t interest you. Only the subject in front of you is worth noting. Isn’t that right?

His tone, nearly arrogant, sounded like a reproach. He went on:

— Right now, you’re thinking about how to get out of this mess. The street no longer seems the strangest place in the world—this little space here does, doesn’t it? You’re thinking how that box of peppers, those abandoned beers, those screams, those cats hiding under the cars, that smoke—none of it compares to the chaos reigning in your head.

— And how can you possibly know all this?

— Martinet’s Elements of General Linguistics upstairs is proof enough that we’ve both sunk into the same wretched solitude.

— Who are you?

— You always choose the side door, never the corridor straight ahead… You’re still thinking in mazes. And yet, since the moment we saw each other just now, you’ve known—we are the same person!

— We’re the same person?

— The same character, yes!

— The same character?

— Don’t look so surprised. Borges—whom you’ve yet to meet—does the same in the first story of The Book of Sand. Dickens—whom you’ve already forgotten—does it with Ebenezer Scrooge. Dante—whom you’re about to discover—dreams of his own soul transmigrating through the circles of Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise.

— And you’ve come to show me the future, is that it? To prove something? That I—we—are wretched? That I need to change so we can both be redeemed?

— I haven’t come to prove anything at all…

My other self bit into the apple, slung his bundle over his shoulder, and stepped back out into the night, unafraid of the deluge, swallowed by the dirty reflection of a thousand shattered lights.

With the Leica off in my hands, I watched him go, unable to add a single word.

Truth be told, there was nothing left to say.

.

From the book O Moscardo e Outras Histórias (The Horsefly and Other Stories, 2018, pp. 255–259)