.

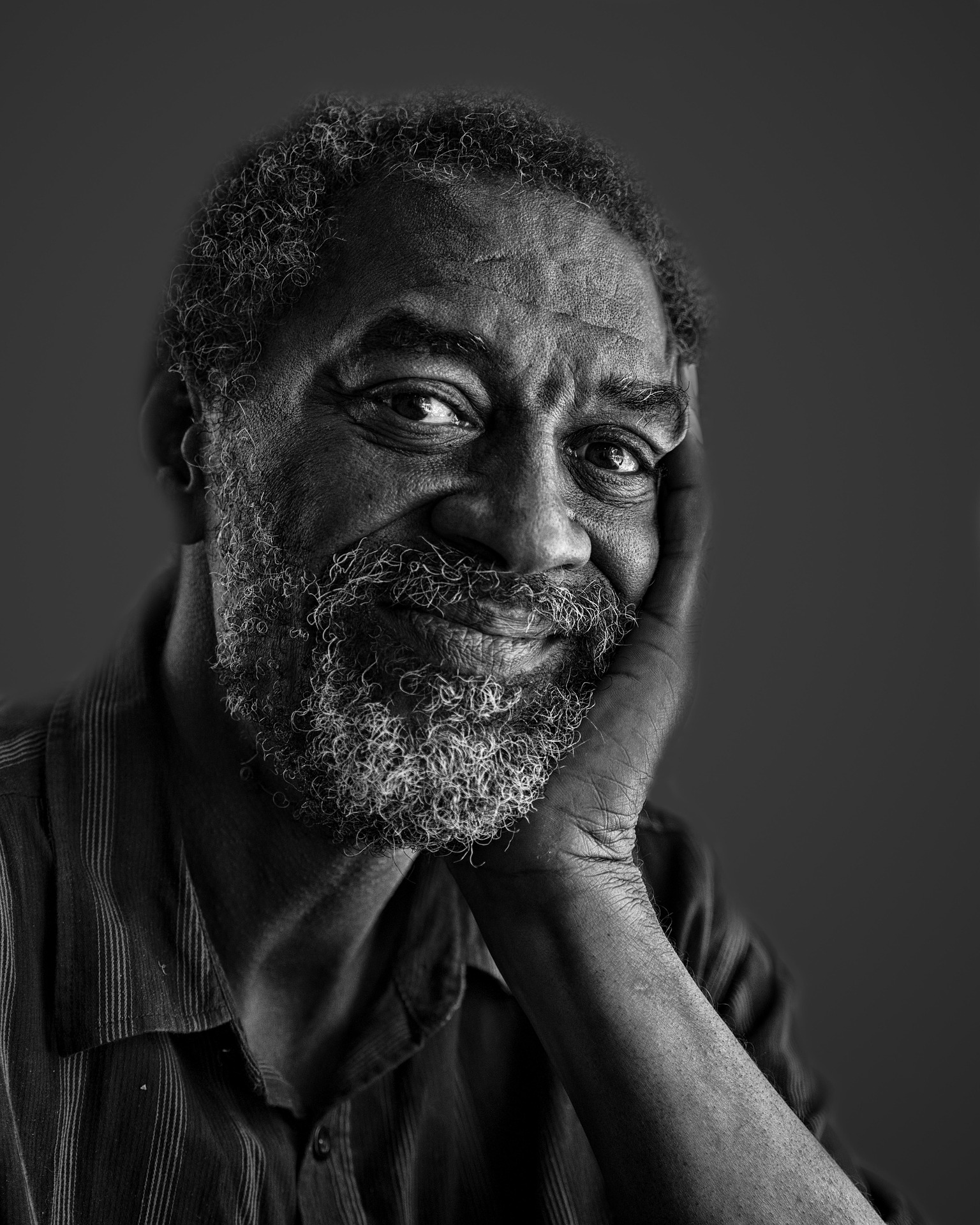

João Ricardo Lopes (Guimarães, 1977) è uno scrittore, poeta e docente portoghese. È autore di una vasta e coerente opera poetica, composta da sette volumi pubblicati, a que se aggiungono una raccolta di racconti e un’antologia di cronache letterarie. Il suo lavoro è stato riconosciuto con importanti premi nazionali e tradotto in diverse lingue, tra cui l’inglese, lo spagnolo, l’italiano e il francese.

La sua poesia si distingue per un tono meditativo e interrogativo, spesso centrato sulla ricerca del silenzio, della redenzione e dell’enigma della condizione umana. Lontana da ogni lirismo ornamentale, la sua scrittura si nutre di una tensione filosofica profonda, con richiami espliciti o sottili al pensiero di Schopenhauer, Sartre, Camus e Cioran.

Lopes coltiva inoltre un costante dialogo con altre forme artistiche, in particolare la musica e la pittura, che assumono un ruolo strutturante nella sua visione poetica. Tale inclinazione interdisciplinare si riflette anche nella sua attività critica e saggistica, spesso attenta alle intersezioni tra parola, immagine e suono.

Vive e lavora a Fafe, nel nord del Portogallo, dove insegna lingua e letteratura portoghese. Il suo impegno educativo accompagna da anni una riflessione etica ed estetica sulla funzione della poesia nel mondo contemporaneo.

•

IL FUOCO DEI GITANI

per Catarina

.

nel sud di Lanzarote, vicino a Playa Blanca,

in un luogo che chiamano Los Charcones,

ho visto ciò che più somiglia, sulla terra,

alla luna

il paesaggio è coperto di piroclasti, di cenere dura,

di polvere.

qui non sopravvive nulla, tranne l’euforbia strisciante

e qualche specie di lucertola

ma di notte questo deserto si riempie di fuochi,

di piccole fiamme sparse

tra muri e tende

dicono sia il fuoco dei gitani,

nessuno sa da dove vengano o dove vadano.

e io dico: siano benedetti, perché esistono

Poema tratto dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

O LUME DOS CIGANOS

para a Catarina

.

no sul de Lanzarote, perto de Playa Blanca,

num lugar a que chamam Los Charcones,

vi o mais parecido que há na terra

com a lua

a paisagem cobre-se de piroclastos, de cinza dura,

de pó.

nada aqui sobrevive, exceto a rasteira eufórbia

e uma ou outra espécie de lagarto

mas à noite este deserto enche-se de fogueiras,

de pequenas labaredas dispersas

entre muros e tendas

explicam é o lume dos ciganos,

ninguém sabe de onde vêm ou para onde partem.

e eu digo abençoados sejam, porque existem

Testo originale in portoghese: dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

SOLSTIZIO D’ESTATE, ROMA

tra le tende

il sole insiste ed entra. quel che di lui

ci scalda sul davanzale

è un riflesso velato

del paradiso.

la luce copre la pelle

e la spoglia,

ricuce,

l’addolcisce senza paura.

è questo il tempo: un misto

amaro e dolce, di brivido solitario

e di tenerezza

Poema tratto dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

SOLSTÍCIO DE VERÃO, ROMA

por entre as cortinas

o sol insiste e entra. o que dele

no parapeito nos aquece

é um resquício velado

do paraíso.

a luz cobre a pele

e despe-a,

sutura,

amacia-a sem medo.

é isto o tempo: uma mescla

amarga e doce, de arrepio solitário

e desvelo

Testo originale in portoghese: dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

MATTINE DI ASSISI

O que nos chama para dentro de nós mesmos

é uma vaga de luz, um pavio, uma sombra incerta.

Fiama Hasse Pais Brandão

.

la santità di questo luogo è la luce,

il bianco che si solleva dalle mura e non si lascia imprigionare

da nulla

di questa luce parlo in altri poemi, e a proposito di altre città

non sarà più che la chiarezza di una margherita,

o il bagliore del finocchio selvatico,

più che una finestra socchiusa sul nascondiglio

delle memorie,

più che un camminare di pietre dove si va a piedi

la luce, questa luce limpida di Assisi, è un silenzio

levita con il suo peso casto, e consola.

e non ci sono parole per lei, non ci sono

Poema tratto dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022).

.

MANHÃS DE ASSIS

O que nos chama para dentro de nós mesmos

é uma vaga de luz, um pavio, uma sombra incerta.

Fiama Hasse Pais Brandão

.

a santidade deste lugar é a luz,

o branco que se eleva das muralhas e se não deixa prender

a nada

dessa luz falo noutros poemas e a propósito de outras cidades

não será mais do que a claridade de um malmequer,

ou o fulgor do morrião dos campos,

mais do que uma janela entreaberta para o esconderijo

das memórias,

mais do que um caminhar de pedras por onde se vai a pé

a luz, esta luz límpida de Assis, é um silêncio

levita com o seu peso casto e acalenta.

e não há palavras para ela, não há

Testo originale in portoghese: dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

ROSSE ROSE, AGAPANTI BLU

niente ora è più bello

del rosso delle rose,

degli agapanti blu sopra la terra

niente è più sublime

della nebbia brevissima

che precede le cose e annuncia l’estate

quell’istante

in cui la luce cade più compatta e la strada gira

e le ringhiere sorreggono l’insopportabile piccolezza

del mondo

quell’istante

in cui gli occhi volano come sassi

e non sanno nemmeno

da che parte stanno volando

Poema tratto dal libro Eutrapelia (2021)

.

ROSAS VERMELHAS, AGAPANTOS AZUIS

nada mais belo agora

do que o vermelho das rosas,

do que os agapantos azuis sobre a terra

nada mais sublime

do que o nevoeiro brevíssimo

que antecede as coisas e anuncia o verão

esse instante

em que a luz cai mais junta e a estrada roda

e as grades amparam a insuportável pequenez

do mundo

esse instante

em que os olhos voam como pedradas

e não sabem sequer

para que lado voam

Testo originale in portoghese: dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

AGOSTO

su frágil armazón de inseguros instantes

José Luis García Martín

.

dovrei parlarti della madreperla,

di quanto splendano i corpi iridescenti,

senza scordare la chitina dello scarabeo,

o la macchia iridescente dell’olio

dovrei dirti quanto mi affascinano

le forme segrete del quarzo,

del sale, delle biglie

o questo verde azzurrato del mare

che mi punge come crisocolla tra le dita,

questo blu dove gli occhi si addormentano

e incerti gelano nel silenzio

questo punto preciso

dove l’infimo e l’infinito stillano l’attimo

e si fanno vetro

Poema tratto dal libro Eutrapelia (2021)

.

AGOSTO

su frágil armazón de inseguros instantes

José Luis García Martín

.

deveria falar-te do nácar,

de como são belos todos os corpos iridescentes,

sem esquecer a quitina do escaravelho,

ou a mancha de combustível

deveria contar-te o quanto me intrigam

as formas interiores do quartzo,

do sal, dos berlindes

ou este verde azul do mar

ferindo-me como crisocola entre os dedos,

este azul onde os olhos adormecem

e indecisos gelam em silêncio

este ponto exato

em que o ínfimo e o infinito segregam o instante

e em vidro solidificam

Testo originale in portoghese: dal libro Eutrapelia (2021)

.

•

IN NOME DELLA LUCE

perdona, perdona tutto.

in nome dei mattini freschi,

dei giorni caldi, in nome delle erbe

che sono solo erbe, ma valgono

il tuo poema, in nome delle voci pristine

degli uccelli che si impadroniscono della terra,

in nome della luce

perdona. perdona tutto

Poema tratto dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

EM NOME DA LUZ

perdoa, perdoa tudo.

em nome das manhãs frescas

dos dias quentes, em nome das ervas

que são ervas, mas valem

o teu poema, em nome das prístinas vozes

dos pássaros que se assenhoreiam da terra,

em nome da luz

perdoa. perdoa tudo

Testo originale in portoghese: dal libro Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

UN GIORNO CONCRETO

chiesero a Ludwig Wittgenstein se quello fosse un giorno concreto

cos’è un giorno concreto?

che cazzo è, un giorno concreto?

non ho mai saputo quale fu la risposta dell’austro-inglese

un giorno concreto.

concreto come un campo di zizzania o di cicuta davanti a noi.

concreto come Tōru Takemitsu in Nostalghia.

concreto come l’odore della serratella, della cipolla o della gomma da masticare nella tua bocca.

concreto come un bicchiere d’acqua sul tavolo

un giorno concreto come restare svegli davanti a un grande orologio da parete.

come incrociare lo sguardo che ci osserva dallo specchio

un giorno concreto come il bruciore alla vescica.

come far rotolare una pietra tra le dita

un giorno concreto come tossire senza grazia per via della polvere.

come scrivere su un foglio infinito la sequenza di Fibonacci

come toccare un sedere.

come sentire il soffritto che prende fuoco

un giorno passato tra il maestrale gelido e la luce che brucia.

un giorno concreto.

ad ascoltare i grilli o a pulirsi le cispe dagli occhi.

concreto come preparare un’insalata con scarola, rucola o lattuga.

come leggere in piedi Bernardo Atxaga o Philip Levine.

o fumare una brutta copia di un Cohiba.

come sbraitare al telefono con qualcuno per le spese del condominio

un giorno concreto.

concreto come tutti i giorni concreti, pieni di fretta e lentezza,

con le mani in tasca, nei guanti, sulla pelle,

pronte a stringere il quaderno e storpiare un’altra poesia

un giorno concreto come amare Le Quattro Stagioni di Vivaldi

e non avere altro da aggiungere.

concreto come avere la barba lunga e nessuna lametta o sapone in casa,

né voglia di radersi quel volto stanco, quasi di nuovo bambino.

concreto come l’autocommiserazione.

come ascoltare alla radio la Quarta di Brahms diretta da Bernstein.

concreto come una mela, al contrario: obclava, svanita.

come il gemito succubo nel coltello che la taglia in due, in quattro.

concreto come prendere un pugno o un paio di corna,

e camminare per settimane con le ossa dolenti.

concreto come i sacchi di tela sulle spalle di uno straccivendolo.

come il tanfo di un animale in decomposizione sull’asfalto.

concreto come il riflesso della pioggia e il peso di un bacio sulle guance

torniamo dunque all’inizio:

chiesero a Wittgenstein, credo sia stato Bertrand Russell,

mentre succhiava la pipa:

cosa significa per lei un giorno concreto?

uno pensava all’ipotetico ippopotamo nascosto tra i mobili del salotto.

l’altro rifletteva su materia e antimateria, sulla lettera che avrebbe scritto

a Niels Bohr

cosa significa per lei un giorno concreto?

era una chiacchierata da filosofi.

e, come si può facilmente sospettare, non arrivarono a nessuna conclusione

Poesia inedita

.

.

UM DIA CONCRETO

perguntaram a Ludwig Wittgenstein se aquele era um dia concreto

o que é um dia concreto?

o que é a porra de um dia concreto?

nunca soube a resposta que deu o austro-inglês

um dia concreto.

concreto como um campo de cizânia ou de cicuta à nossa frente.

concreto como Tōru Takemitsu em Nostalghia.

concreto como o cheiro da serralha ou de uma cebola ou do chewing gum na tua boca.

concreto como um copo de água sobre a mesa

um dia concreto como estar acordado diante de um grande relógio de parede.

como olhar nos olhos os olhos que nos olham ao espelho

um dia concreto como sentir ardor na bexiga.

como ter uma pedra a rolar entre os dedos

um dia concreto como tossir sem blandícia por causa do pó.

como escrever numa folha interminável a sequência de Fibonacci.

como apalpar um traseiro.

como sentir o estrugido a queimar

um dia passado entre o frio mistral do vento e o abrasador da luz.

um dia concreto.

a escutar grilos ou a limpar ramelas.

concreto como fazer uma salada com escarolas ou rúcula ou alface.

como ler de pé Bernardo Atxaga ou Philip Levine.

ou fumar uma imitação barata de um Cohiba.

como vilipendiar alguém ao telefone por causa do condomínio

um dia concreto.

concreto como todos os dias concretos, cheios de pressa e de vagar,

mãos nos bolsos, nas luvas, na pele,

prontas a segurar o caderno e a estropiar mais um poema

um dia concreto como amar as Quatro Estações de Vivaldi

e não ter mais que dizer.

concreto como ter a barba crescida e nenhuma lâmina ou sabão em casa,

nem vontade para escanhoar o atordoado rosto, quase de novo infantil.

concreto como a autocomiseração.

como ouvir na rádio a Quarta de Brahms conduzida por Bernstein.

concreto como uma maçã, ao contrário, obclávea, tonta.

como o gemido súcubo dentro da faca que a corta em dois e em quatro.

concreto como levar um murro ou um par de cornos

e andar semanas, magoadamente, a cair sobre os ossos.

concreto como sacos de lona às costas de um farrapeiro.

como o fedor de um animal em decomposição sobre o asfalto.

concreto como o reflexo da chuva e o peso de um beijo sobre as faces

voltemos, portanto, ao começo:

perguntaram a Wittgenstein, creio que foi Russell quem o fez,

enquanto alambazava o cachimbo

o que é para si um dia concreto?

um indagava no putativo hipopótamo escondido entre os móveis da sala.

o outro meditava em matéria e antimatéria, na carta que haveria de escrever

a Niels Bohr

o que é para si um dia concreto?

era uma conversa fiada, de filósofos.

a nenhuma conclusão chegaram, como é fácil, aliás, de suspeitar

Testo originale (inedito) in portoghese

.

•

Biografia dell’autore, selezione dei testi e traduzione di Fabrizio Poli.

.