.

He had acquired the habit of meticulously washing his hands and trimming his nails before delivering a speech. He ran his palms and the backs of his fingers under the water, lathered them with Clarim, then held them again beneath the stream flowing from the tap, almost scalding hot. It was a ritual.

Then, before leaving his office, he read the text one last time and corrected it with a cheap pencil, crossing out more words than he put back onto the page. He disliked coming up against formulas, clichés, sentences that sounded like a great deal and yet said nothing.

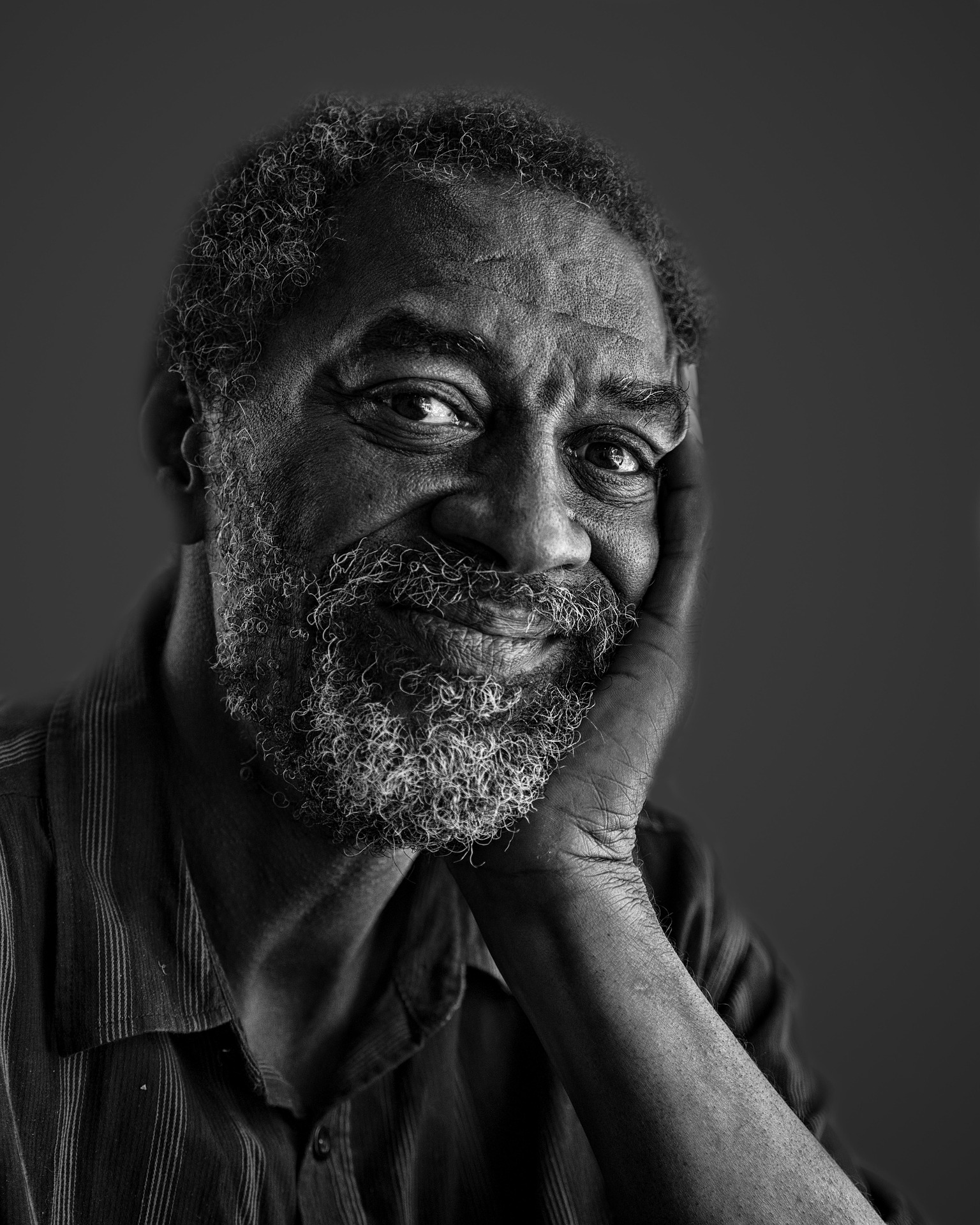

Finally, he looked at himself in the mirror.

He did so in silence, trying to glimpse in the face before him the slightest traces of childhood. He searched there for the boy in clogs, with a torn sweater and an ugly little moustache, whose courage in the hard work of those earlier days he seemed to value more than the prestige he had gained over the years. That boy was his inspiration.

He remained in near-total silence for a long time, an immeasurable stretch, an hour, a minute, an eternity, until an aide knocked at the door.

They were waiting for him.

This was the moment. Millions of viewers had their televisions tuned to the channel through which his words would echo, measured, carefully chosen, perhaps a little rough, competent, in a steep dive toward the very core of the problems.

.