.

REMBRANDT’S SADNESS

the question was always this:

can someone’s sadness, at any time, in any place,

ever find a way to be satisfied?

we have our doubts about the matter

sadness shares with water the sin of avarice.

first it skips about, then it digs itself in,

and a little further on it hollows out sombre lights

through the hills,

one day it cuts across our path

“you shall not pass,” it writes under its breath,

“you shall not pass”

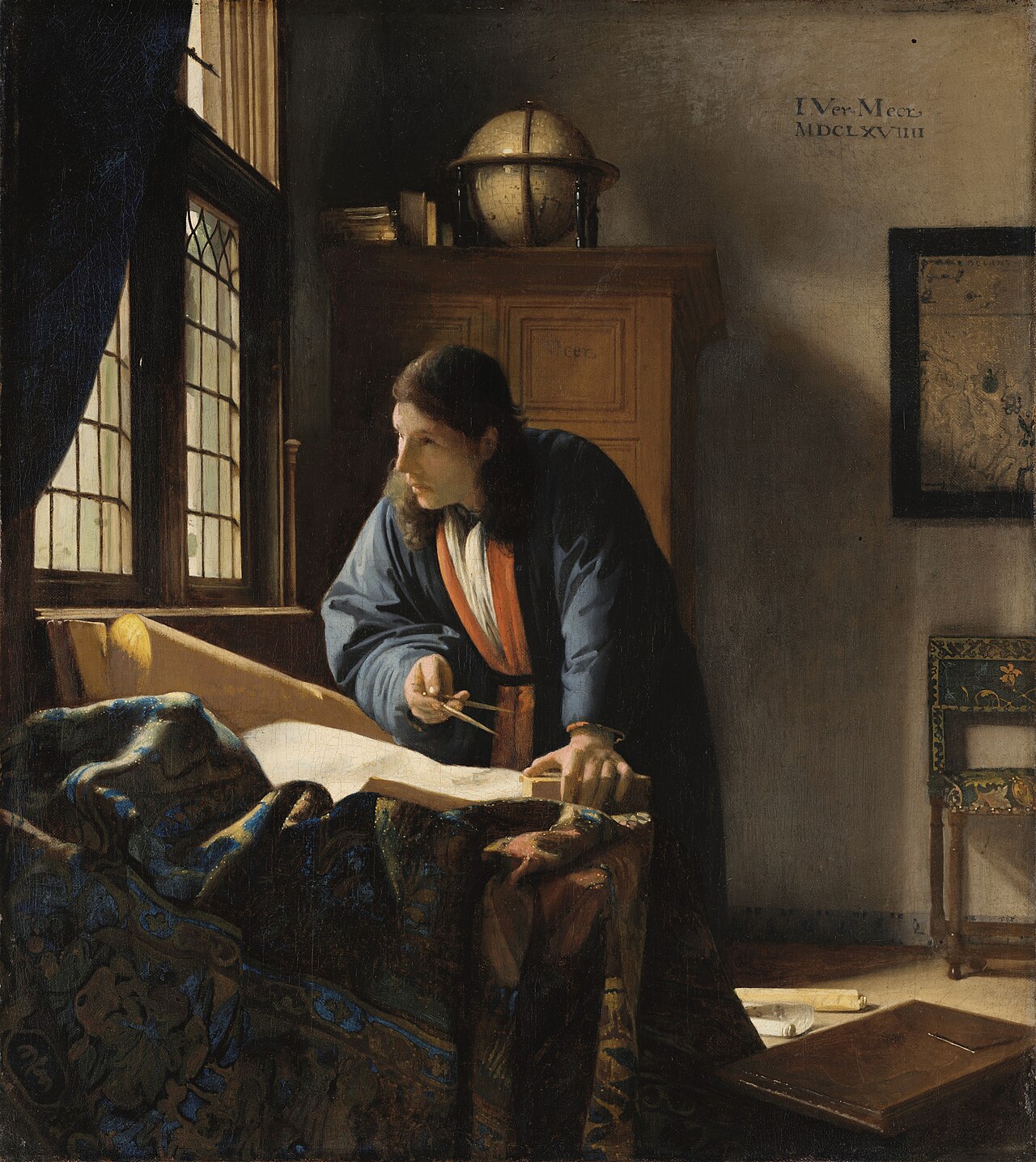

let us consider the case of Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

his pain seems limitless, growing from portrait

to portrait, like a river that knows itself unstoppable

in its predatory course

looking into his eyes as they look into the mirror,

we see Saskia and the promissory notes, old age imprinted

in the swellings and the cracks of the skin

what is the size or the depth of his grief?

we have an idea about the matter,

water is a good term of comparison

one day it makes us sink into a delirium of silver‑gelatin paper.

but not even there, not even then, does it show itself fully sated.

sadness will not abide the earth’s crust,

its kingdom lies in the deepest hells,

or even beyond them

.

A TRISTEZA DE REMBRANDT

a questão foi sempre essa:

pode em algum momento, nalguma parte, a tristeza

de alguém satisfazer-se de alguma forma?

temos as nossas dúvidas sobre o assunto

a tristeza partilha com a água o pecado da avareza.

primeiro saltita, logo depois entrincheira-se,

um pouco mais à frente escava luzes sombrias

por entre as colinas,

um dia corta-nos o caminho

«não passarás» escreve em surdina,

«não passarás»

vejamos o caso de Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn

a sua dor parece ilimitada, cresce de retrato

em retrato, como um rio que se conhece imparável

na marcha predatória

olhando os seus olhos olhados ao espelho,

vemos Saskia e as notas de dívida, a velhice estampada

nos inchamentos e nas gretas da pele

qual o tamanho ou a profundidade do seu desgosto?

temos uma ideia sobre assunto,

a água é um bom termo de comparação

um dia faz-nos submergir num delírio de papel gelatina

de prata.

mas nem aí, nem assim, se mostra ela inteiramente saciada.

a tristeza não a suporta a crusta terrestre,

o seu reino é nos infernos mais ínferos,

ou mesmo para além deles

(2026)

.