.

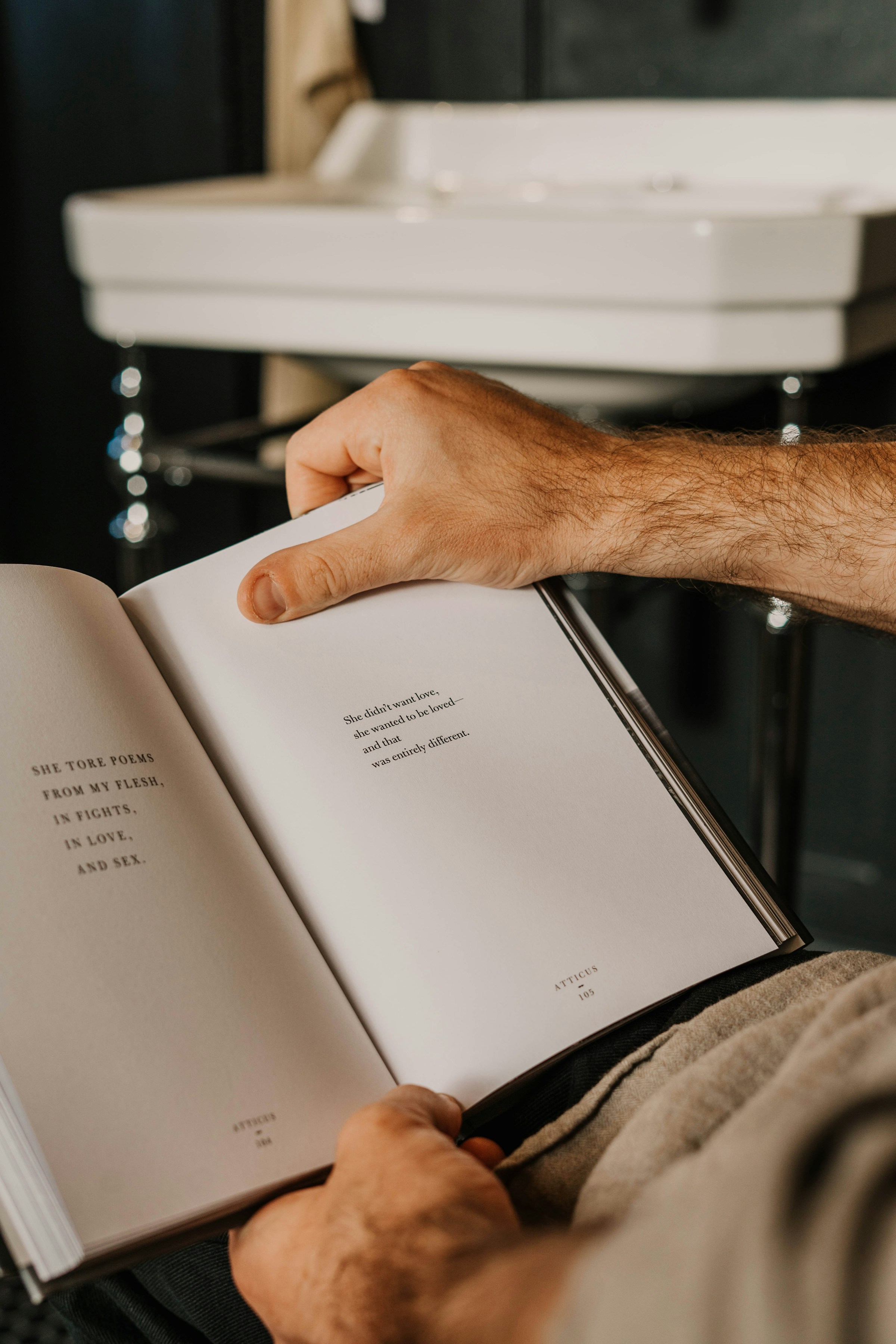

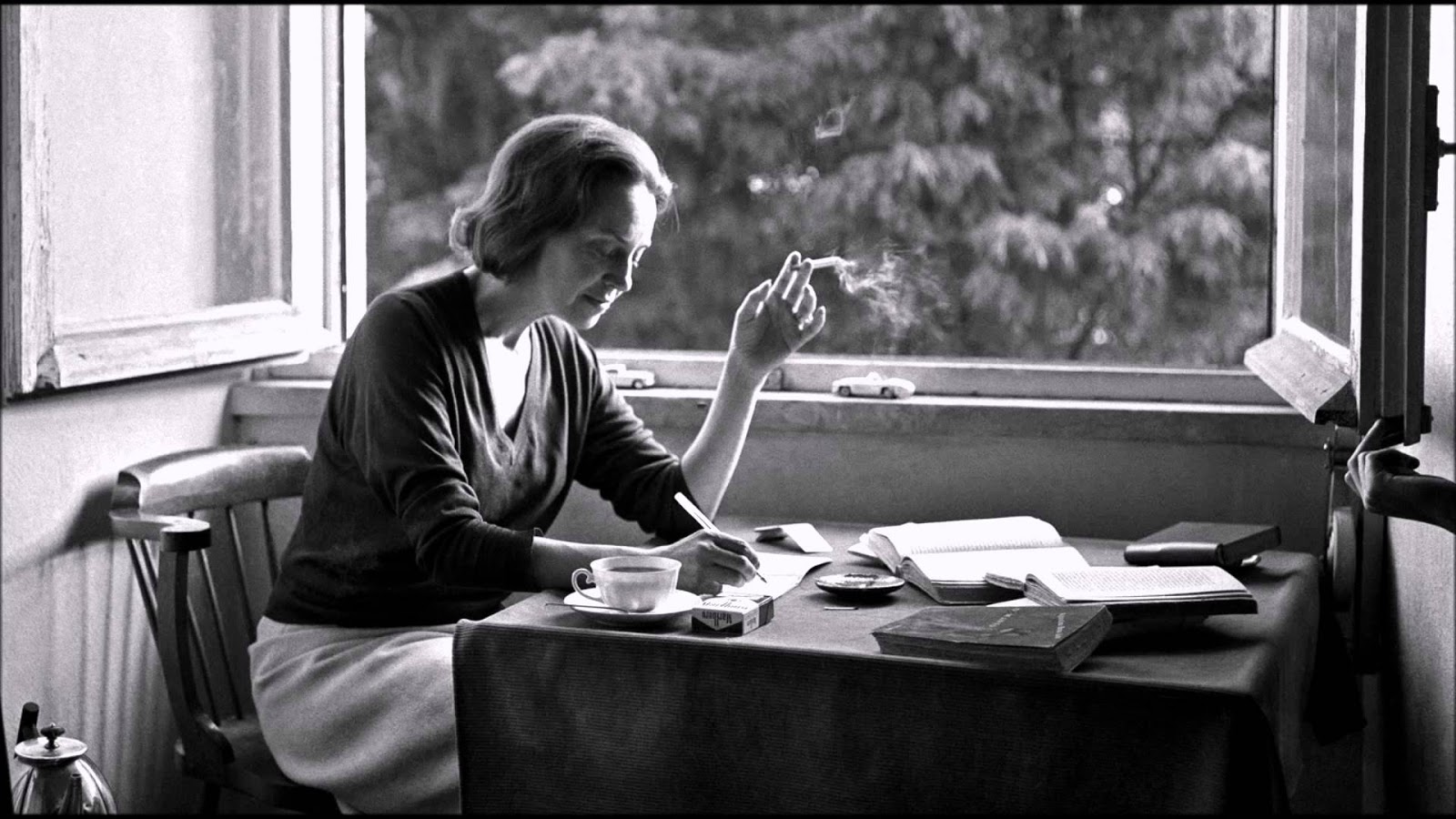

In one of the poems of No Tempo Dividido, Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen writes, in the manner of an inscription: “Que no largo mar azul se perca o vento / E nossa seja a nossa própria imagem” — “That in the wide blue sea the wind be lost / And ours be our own image.”

The pelagic world was for the poet, as is commonly known, a demiurgic, almost religious space, from which emerged her creative force, her fascination with ancient time (which was equally her fascination with the inscrutable future), but also her most personal delight in the peoples who, having sailed those seas of a remote past (the Greeks, in particular), bequeathed to us their art, their beauty, their nude, and within them (as in Heidegger’s ontology) our destiny.

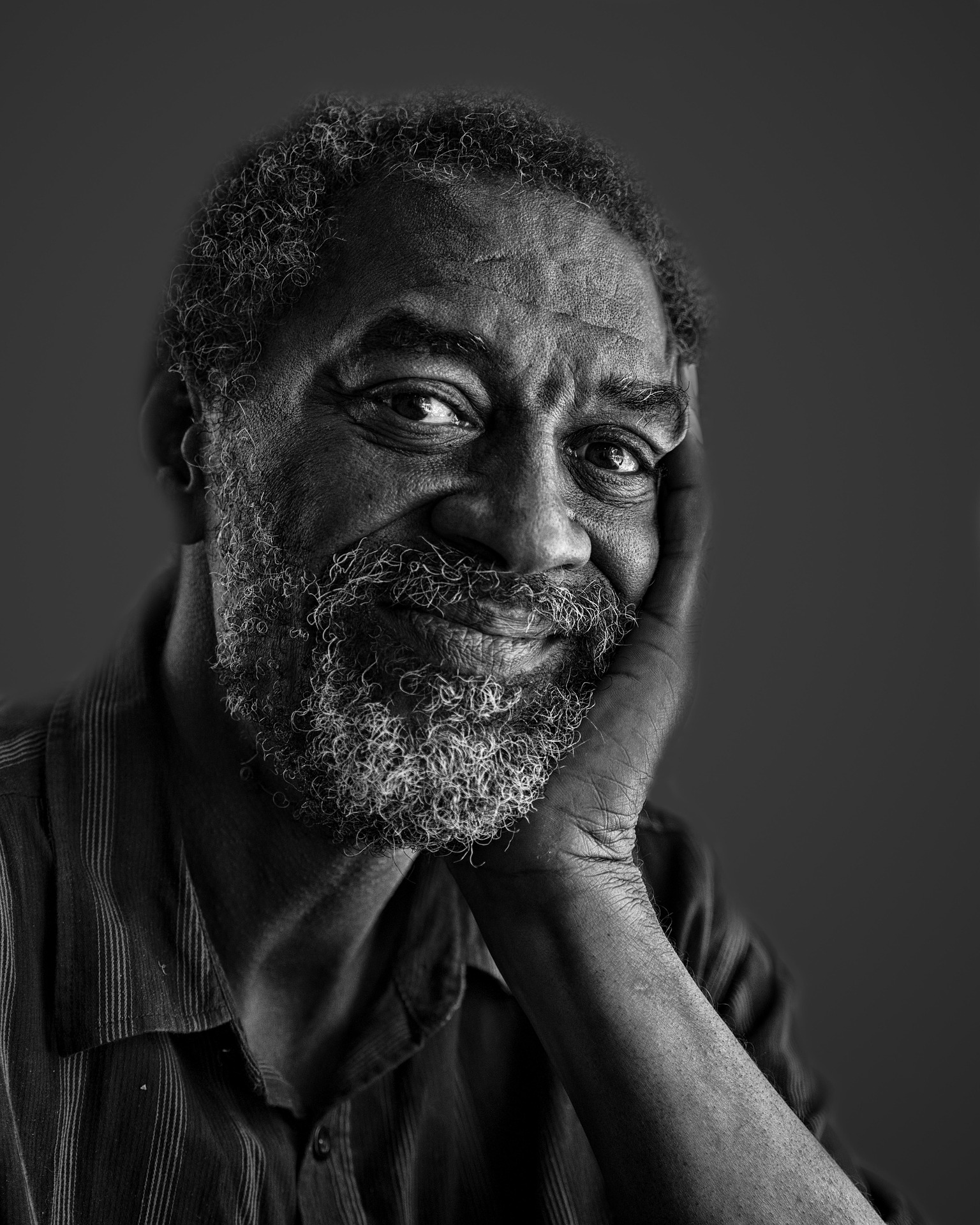

Sophia’s poems are, without exception, exercises in incomparable lapidary art. We read them today under the relative oblivion to which every work is consigned after the death of its author. Yet for this very reason we rediscover them as more vehement, more marvellously sculpted, more true. We read them as an extension of ourselves, as though seated on a garden bench among the twisted trunks of giant trees (like these metrosideros in Foz do Douro), the wide blue sea before us seemed more real, and our own spirit wandered amid those waves and the scent of the sea breeze, while between the seated body and the wandering spirit there existed something unnameable. Something like our own image, doubly beheld in the mirror.