.

VERMEER

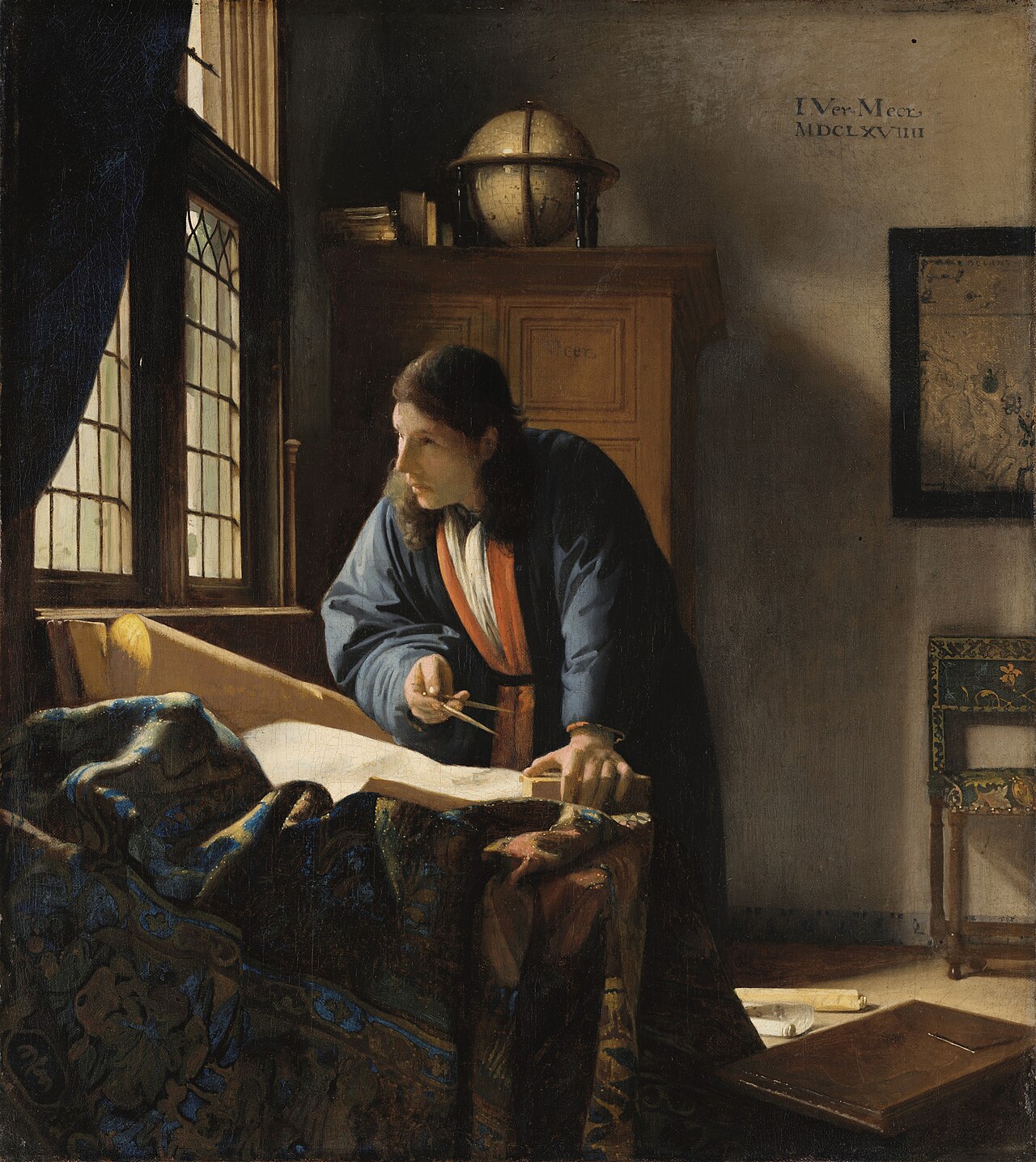

in these days of vertigo, when the world seems to go mad with every gunshot, and even open books are grasping mouths waiting for impure truths to be spoken through them, I return to Vermeer’s silent paintings: to the milkmaid pouring the white unhurriedly, imbued with grace; to the geographer who, through the panes of glass, discerns the inexact place of thought; to the girl reading the mysterious letter, in which she may be shown a certain love, not delicate like a poem, but in the hardness of verbs that do not hide in grammar and instead strip themselves bare in living gestures, difficult and unfeigned

.

VERMEER

nestes dias de vertigem em que o mundo parece ensandecer a cada disparo e até os livros abertos são bocas avaras à espera de que por eles se digam as impuras verdades, volto aos quadros silenciosos de Vermeer, à leiteira vertendo o branco sem pressa, eivada de garbo, ao geógrafo que descortina pelos vidros o inexato lugar do pensamento, à rapariga que lê a carta misteriosa, na qual talvez lhe seja mostrado um certo amor, não delicado como um poema, mas na dureza dos verbos que se não escondem na gramática e antes se desnudam em gestos vivos difíceis e não hipócritas

.