.

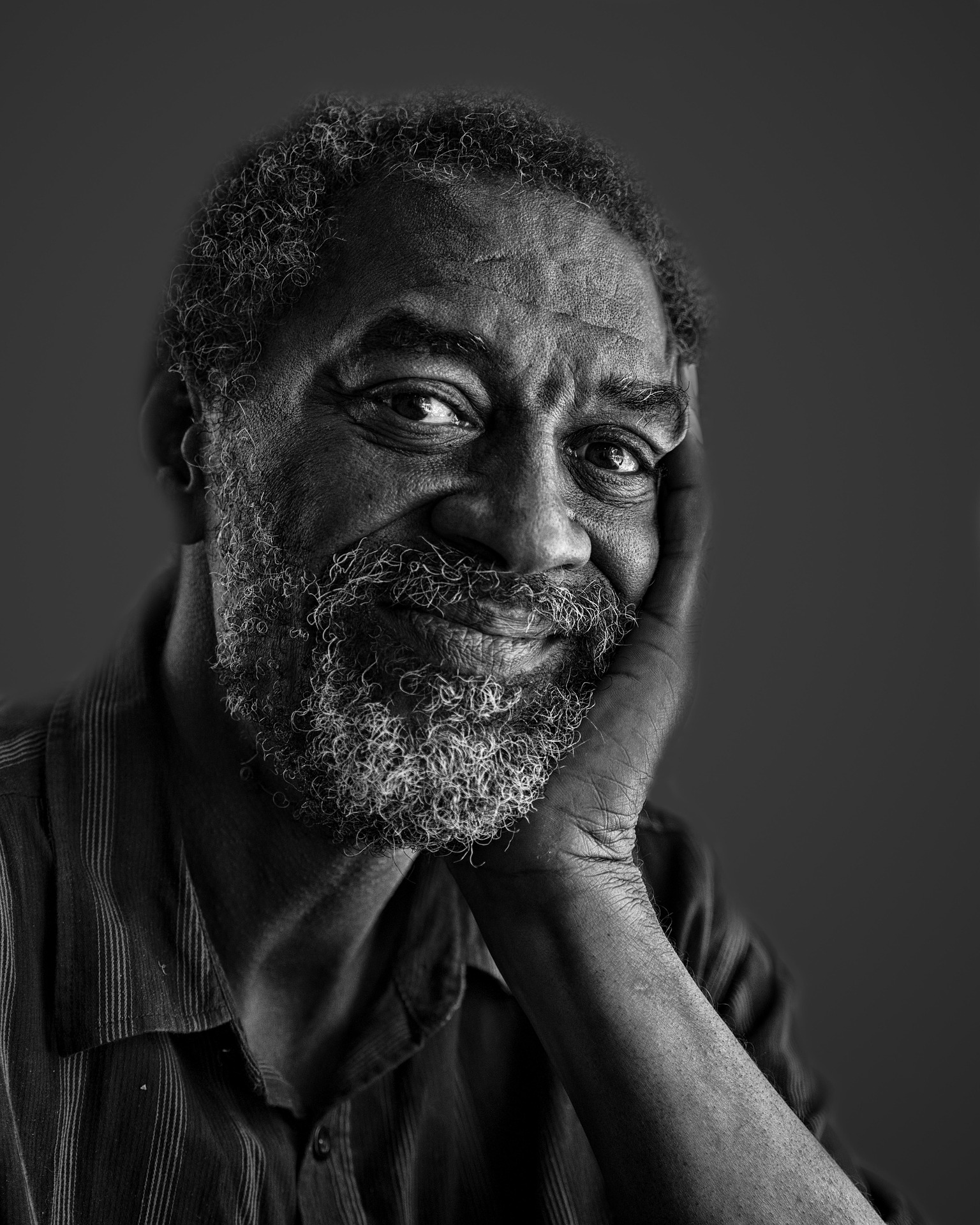

They brought him ivory, and he carved it with the most refined patience of which the human kind is capable. The objects that came from his hands were among those most ravenously coveted by foreigners in Brazzaville, in Djambala, in Sibiti, in Mandigou, and throughout the Congo. They called him “The Blessed One,” though his real name was Isidor Nkobanjira. As he grew old, he boasted of having no fewer than seventy children.

Near the end, he began to cut and pierce and carve deep grooves into an elephant tusk. First, he etched the winding course of a river, then the rise of a mountain, then a flurry of perfectly hemispheric stars. With care, he added water and fish, earth and impalas, sky and vultures. He filled the ivory with every creature he could remember, omitting neither silence, nor death, nor fear.

“The whole universe fits here,” Nkobanjira thought.

But in truth — he noticed with a look of dissatisfaction — after all was done, a bit of space still remained.