.

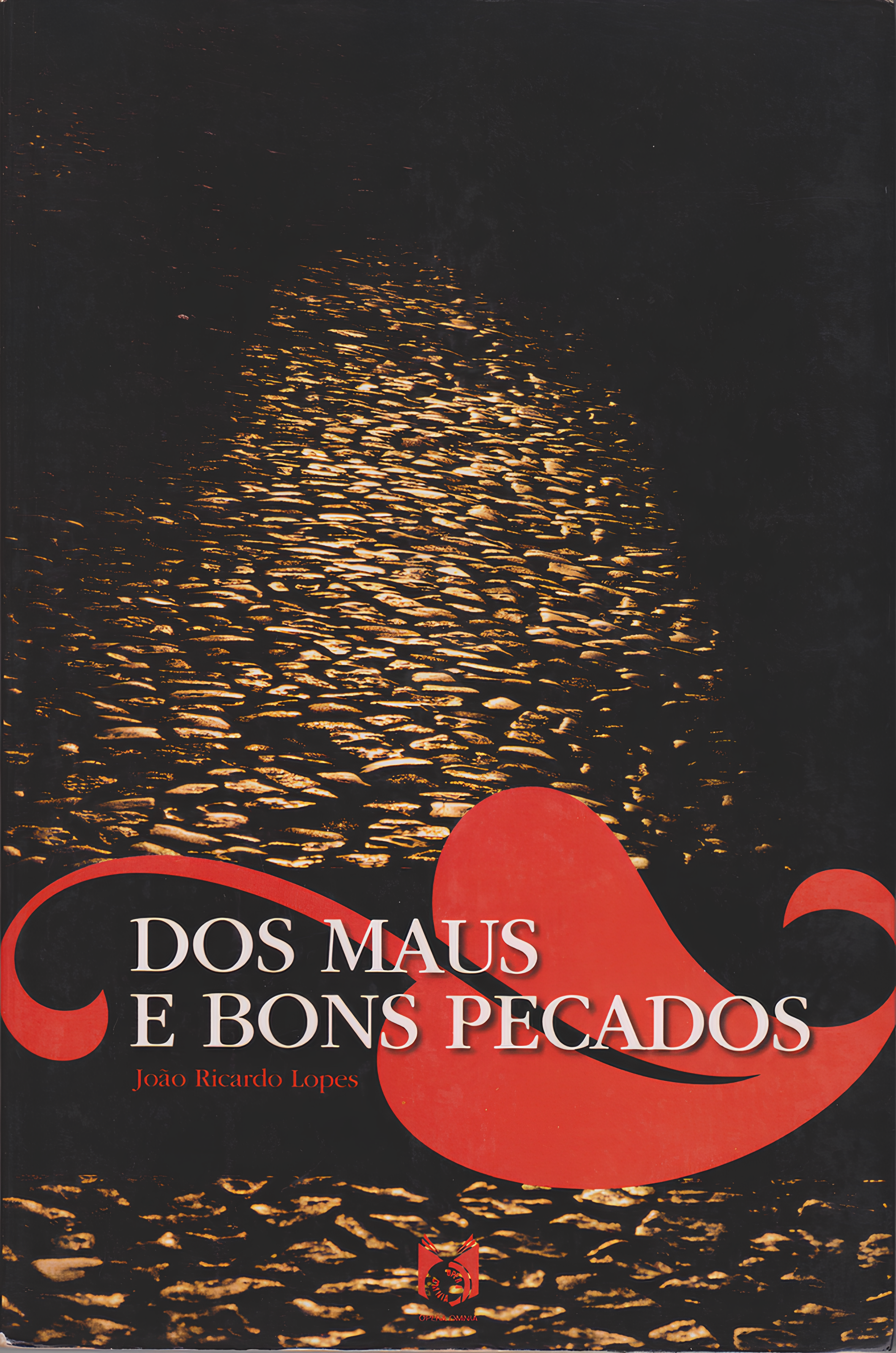

In 2007, following several years of collaboration with various newspapers, João Ricardo Lopes brought together a selection of previously published texts in the volume Dos Maus e Bons Pecados (On Sins, Both Good and Bad). This collection represents not merely a compilation of occasional writings, but a cohesive literary project in which the author reaffirms his dual allegiance to poetic sensibility and a prose style closely aligned with fictional narrative.

While maintaining his commitment to poetic expression, Lopes draws upon a range of thematic materials rooted in the everyday—his personal biography, the social life of his native village, and broader reflections on contemporary experience. Across the fifty-three prose pieces, he orchestrates a subtle interplay between humour and introspection, articulating a voice at once intimate and socially attentive. This balance is indicative of a literary temperament that, although anchored in lyricism, is responsive to the narrative and reflective demands of the genre.

Literary critic Cláudio Lima proposes a tripartite reading of the collection, distinguishing between prose pieces of an autobiographical nature, those that adopt a more engaged stance on cultural and civic matters, and those conceived as fictional exercises. The absence of chronological or thematic ordering, he argues, invites the reader to undertake a hermeneutic task: to trace resonances and continuities—be they experiential, thematic, or temporal—across the body of texts. As Lima observes:

“Not being dated nor ordered according to any discernible principle, it falls to the reader to establish thematic, experiential, or chronological connections while navigating, without instruments, through the liveliness and unpredictability of the prose.”

.

Lima further notes that even the ostensibly fictionalised pieces resist clear categorisation. Few are fully immersed in fiction; rather, a faint current of fictional invention traverses many of them, including those in which Lopes appears most vulnerable or personally exposed. The narrating subject often reflects on the emotional weight of daily life or on the ambivalent presence of women, who emerge as figures of fascination and destabilisation. Particularly striking are two texts—“I Must Have Aged” (p. 21) and “This Nameless Thing of Gazing into the Infinite” (p. 137)—in which the author adopts a female voice, engaging in a kind of literary transvestism. These interior monologues, marked by repetition and lyrical insistence, explore themes of solitude, bodily decline, the waning of desire, and the precariousness of romantic bonds.

Another critical perspective is offered by Artur Ferreira Coimbra, who insists that Dos Maus e Bons Pecados is unambiguously the work of a poet. For Coimbra, the richness of themes across the more than 150 pages of prose reveals a sustained and deeply personal drive towards literary expression:

“The hand that pens Dos Maus e Bons Pecados is unmistakably that of the poet […] The themes and questions raised over the course of more than 150 pages of prose pieces are manifold—testament to an insatiable hunger for writing.”

.

Among the many subjects addressed, Coimbra highlights the evocation of the poet Santiago Rui, “lost to the aridity of daily existence”; meditations on Holy Week; the emotional power of small gestures and natural beauty; philosophical inquiries into happiness; the foundational role of libraries and literature; the praise of friendship as “precious anchors in this world”; and the author’s enduring distaste for bullfighting and the circus. Also notable are autobiographical moments concerning the milestones of adolescence and adulthood, the discovery of fado through Carlos Paredes, the almost mythic struggle of facing Mondays, and the symbolic significance of certain places and months (Foz, January, March).

Equally characteristic is the author’s affection for cats, whose poise and apparent indifference are seen as metaphors for freedom and manipulation. His admitted obsession with moleskines serves as a self-reflexive nod to the compulsions of the writerly life. Elsewhere, Lopes reflects candidly on turning thirty, celebrating the moment with the declaration: “and sod it! I belong to this day, I shan’t work today” (p. 126). Recurring themes include the rituals of São João, the sorrows of pet abandonment, the decline of Latin, and, significantly, the presence of a Roman Muse who both concludes and ignites his writing.

Throughout, the author reveals a profound and poetic attachment to family, especially to his father, mother, and sisters Elsa, Marta, and Catarina. His piece entitled “Mother” is singled out by Coimbra as particularly affecting—“simply enchanting.” As a whole, Dos Maus e Bons Pecados constitutes not only a highly crafted body of work but also a testament to the literary maturity of its author, affirming his place within contemporary Portuguese letters as a writer who reconciles the poetic with the quotidian, memory with invention, and introspection with narrative wit.