.

.

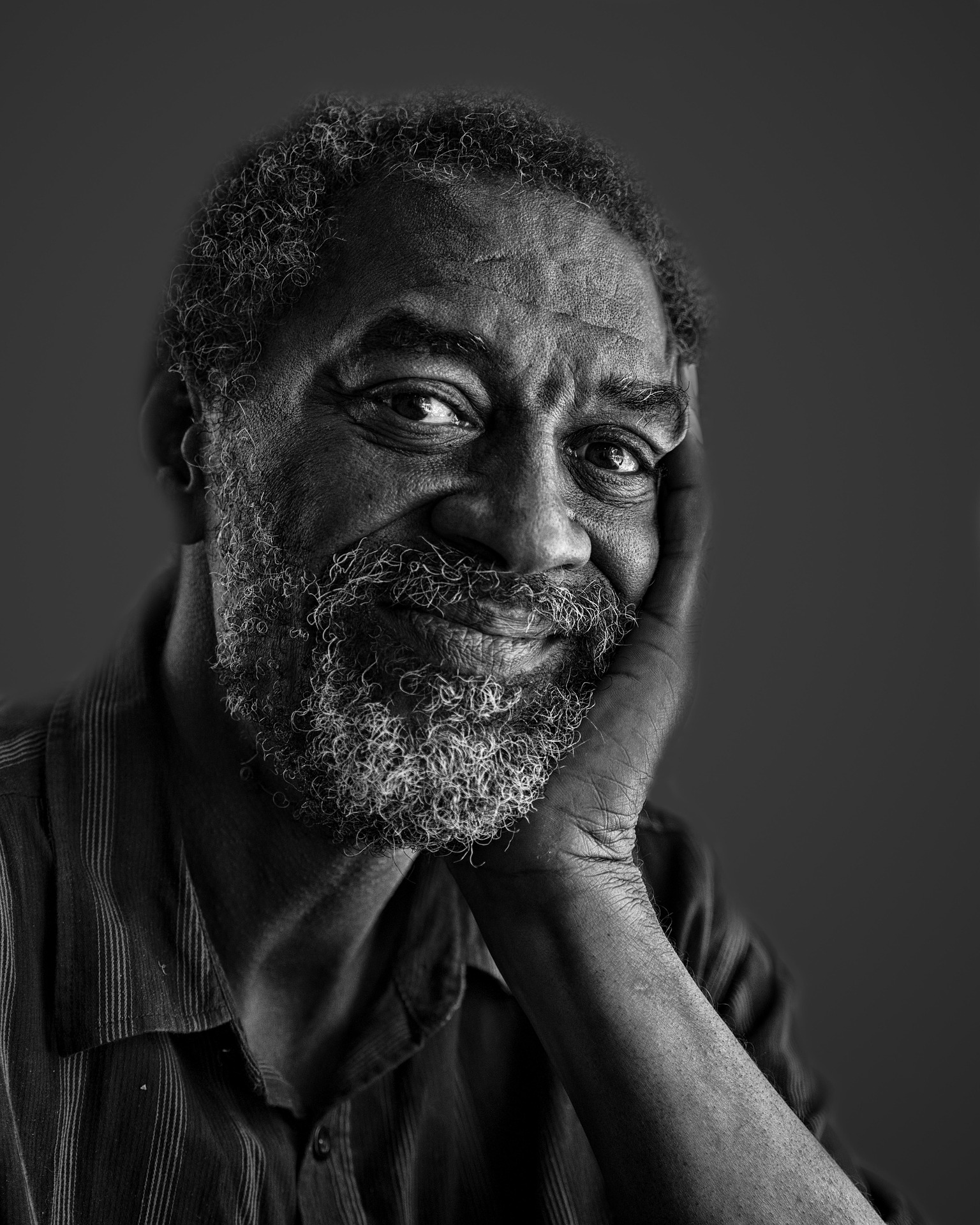

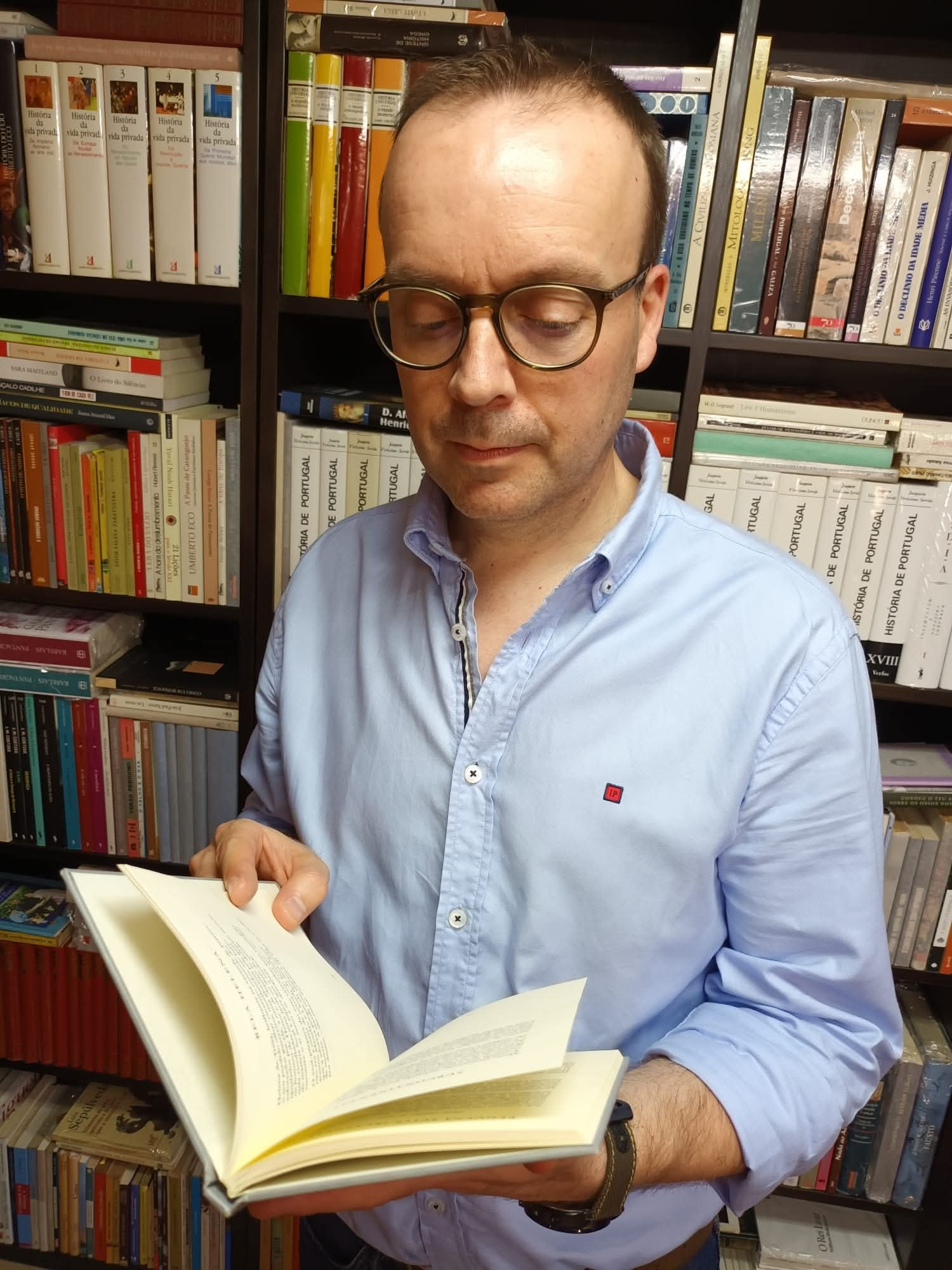

João Ricardo Lopes (Guimarães, 1977) est un écrivain, poète et enseignant portugais. Il est l’auteur d’une œuvre poétique cohérente, composée de sept volumes publiés, auxquels s’ajoutent un recueil de nouvelles et une anthologie de chroniques littéraires. Son travail a été reconnu par d’importants prix nationaux et traduit en plusieurs langues, dont l’anglais, l’espagnol, l’italien et le français.

Sa poésie se distingue par un ton méditatif et interrogatif, souvent centré sur la quête du silence, de la rédemption et de l’énigme de la condition humaine. Éloignée de tout lyrisme ornemental, son écriture s’ancre dans une tension philosophique profonde, avec des échos explicites ou subtils à la pensée de Schopenhauer, Sartre, Camus et Cioran. Malgré la profondeur de sa réflexion, sa poésie n’est pas exempte d’une subtile pointe d’ironie et d’humour, apportant une légèreté inattendue à ses interrogations.

Lopes entretient également un dialogue constant avec d’autres formes artistiques, en particulier la musique et la peinture, qui jouent un rôle structurant dans sa vision poétique. Cette inclination interdisciplinaire se reflète aussi dans son activité critique et essayistique, souvent attentive aux croisements entre le mot, l’image et le son.

Il vit et travaille à Fafe, dans le nord du Portugal, où il enseigne la langue et la littérature portugaises. Son engagement éducatif accompagne depuis des années une réflexion éthique et esthétique sur la fonction de la poésie dans le monde contemporain.

•

À L’INTÉRIEUR DU SILENCE

tu poses le livre sur ton nez pour en respirer l’odeur du papier.

puis tu balbuties des choses indéfinies,

tu te souviens des jeunes filles peintes par Vermeer,

tu absorbes, par les fentes de la maison, comme elles,

l’amour des lettres

tu as trouvé l’intérieur du silence,

cet instant de tarlatane, ou de soie, ou de satin,

où tu ressens dans les choses la tiédeur

que les doigts enveloppent

puis tes lèvres tremblent un peu,

tu dis rien n’est aussi pur,

tu observes, comme une débutante, la promesse du soleil sur l’appui de la fenêtre

et c’est comme si tu rentrais dans un rêve

tu es à l’intérieur de toi.

tu ne sais comment

Extrait du livre Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

NO INTERIOR DO SILÊNCIO

depões o livro sobre o nariz para aspirar-lhe o cheiro do papel.

depois balbucias coisas indefinidas,

lembras-te das raparigas pintadas por Vermeer,

absorves pelos vãos da casa, como elas,

o amor das cartas

encontraste o interior do silêncio,

esse instante de tarlatana, ou de seda, ou de cetim,

em que sentes nas coisas a calidez

que os dedos cobrem

depois tremem-te um pouco os lábios,

dizes nada é tão puro,

observas, como debutante, a promessa do sol no parapeito

e é como se reentrasses num sonho

estás no interior de ti.

não sabes como

De Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

À CINQUANTE ANS

à cinquante ans, on ne se trompe plus sur la qualité d’un poème,

ni sur l’amour d’une femme.

à cinquante ans, règne dans ce que l’on fait

la lumière fixe d’une lampe

on impose des règles :

écouter en voiture Mingus, Davis, Coltrane,

ne lire que Borges et au-delà,

partir,

choisir bien ses ennemis, oublier les médiocres,

écouter le dentiste, promettre à la famille,

entretenir l’espérance

à cinquante ans, la lumière ne voile ni ne révèle,

elle est seulement un lieu vers lequel on va

quand aucun autre ne suffit –

on habite les heures, car le temps aussi

est un lieu où l’on dépose le corps

à cinquante ans, un seul vers parfois suffit.

c’est presque toujours lui qui nous sauve

Extrait du livre Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

AOS CINQUENTA

aos cinquenta já não se confunde a qualidade de um poema,

ou o amor de uma mulher.

aos cinquenta impera nas coisas que fazemos

a luz fixa de uma lâmpada

impomos regras:

ouvir no carro Mingus, Davis, Coltrane,

ler somente de Borges para cima,

ir,

escolher bem os inimigos, esquecer os medíocres,

ouvir o dentista, prometer à família,

acalentar a esperança

aos cinquenta a luz não tapa nem destapa,

é somente um lugar aonde se vai

quando nenhum sítio é capaz

– moramos nas horas, porque também o tempo

é um lugar onde deixamos o corpo

aos cinquenta um só verso às vezes basta.

quase sempre é ele que nos salva

De Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

AU NOM DE LA LUMIÈRE

pardonne, pardonne tout.

au nom des matins frais,

des jours brûlants, au nom des herbes

qui ne sont qu’herbes, mais valent

ton poème, au nom des voix immaculées

des oiseaux qui s’emparent de la terre,

au nom de la lumière

pardonne. pardonne tout

Extrait du livre Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

EM NOME DA LUZ

perdoa, perdoa tudo.

em nome das manhãs frescas

dos dias quentes, em nome das ervas

que são ervas, mas valem

o teu poema, em nome das prístinas vozes

dos pássaros que se assenhoreiam da terra,

em nome da luz

perdoa. perdoa tudo

De Em Nome da Luz (2022)

.

•

ROSES ÉCARLATES, AGAPANTHES AZUR

rien de plus beau à cette heure

que le l’écarlate des roses,

que les agapanthes azur sur la terre

rien de plus sublime

que le brouillard très bref

qui précède les choses et annonce l’été

cet instant

où la lumière tombe plus dense et la route tourne

et les grilles soutiennent la petitesse insupportable

du monde

cet instant

où les yeux volent comme des pierres jetées

sans même savoir

de quel côté ils volent

Extrait du livre Eutrapelia (2021)

.

ROSAS VERMELHAS, AGAPANTOS AZUIS

nada mais belo agora

do que o vermelho das rosas,

do que os agapantos azuis sobre a terra

nada mais sublime

do que o nevoeiro brevíssimo

que antecede as coisas e anuncia o verão

esse instante

em que a luz cai mais junta e a estrada roda

e as grades amparam a insuportável pequenez

do mundo

esse instante

em que os olhos voam como pedradas

e não sabem sequer

para que lado voam

De Eutrapelia (2021)

.

•

ORAGE

au moins cela,

les éclairs pataugeant

dans l’espace,

égayant la nuit,

les tonnerres frappant

aux gonds des portes,

l’odeur de la terre sèche

que les doigts de la pluie

soulèvent.

au moins cela,

sentir quelque chose d’éveillé

en nous et pour nous,

comme un vibrato au piano

que quelqu’un joue

à une heure tardive,

juste à temps pour nous sauver

Extrait du livre Eutrapelia (2021)

.

TROVOADA

ao menos isso,

os relâmpagos chafurdando

no espaço,

alegrando a noite,

os trovões percutindo

nos gonzos das portas,

o cheiro da terra seca

que os dedos da chuva

levantam.

ao menos isso,

saber algo acordado

em nós e para nós,

como um vibrato ao piano

que alguém toca

a horas tardias,

mesmo a tempo de nos salvar

De Eutrapelia (2021)

.

•

SOLSTICE EN CRÈTE, PALAIS DE CNOSSOS

à Catarina

.

nous aimerons à jamais cette lumière limpide de Crète

qui, au palais de Minos, éclaire les poissons et le taureau

et toutes les formes que notre existence labyrinthique

a emprisonnées

éblouis ou aveugles, nous voyons encore comme des ombres chromatiques

le blanc des pierres, le rouge pompéien,

le bleu cyan des fresques, le jaune moutarde,

l’orange acidulé des visages et des corps,

l’ocre des amphores dressées en offrande aux dieux

le temps peut (comme on crache les pépins amers) nous rejeter,

mais nous avons vu la vie et à un miracle

très ancien

nous remercions le soleil de ce jour

Extrait du livre Eutrapelia (2021)

.

SOLSTÍCIO EM CRETA, PALÁCIO DE CNOSSOS

para a Catarina

.

amaremos para sempre essa luz límpida de Creta

que no palácio de Minos os peixes ilumina e o touro

e todas as formas que a nossa existência labiríntica

aprisionou

ofuscados ou cegos, vemos ainda como sombras cromáticas

o branco das pedras, o vermelho-pompeia,

o azul ciano dos afrescos, o amarelo-mostarda,

o laranja cítrico dos rostos e dos corpos,

o ocre das ânforas erguidas em oferecimento aos deuses

pode o tempo (como se faz a pevides amargas) cuspir-nos,

mas nós vimos a vida e a um milagre

antiquíssimo

agradecemos o sol deste dia

De Eutrapelia (2021)

.

•

PAVANE, RAVEL

And death is real, and dark, and huge.

John Updike

.

tomber en nous-mêmes

sans bruit

comme tombent sur la terre

les insectes.

rester dans le silence,

pesant la douleur

ou les euphories vaines.

croire à la netteté

des choses,

surtout maintenant

que se comprend

la dimension de l’abîme

Extrait du livre Eutrapleia (2021)

.

PAVANA, RAVEL

And death is real, and dark, and huge.

John Updike

.

cair dentro de nós mesmos

sem rumor

como caem na terra

os insetos.

permanecer no silêncio,

sopesando a dor

ou as vãs euforias.

acreditar na lisura

das coisas,

sobretudo agora

que se compreende

a dimensão do abismo

De Eutrapelia (2021)

.

•

MAISON DES GRANDS-PARENTS

dans les greniers tombait l’air épais de l’après-midi,

la lumière claire et tiède de juin,

parfois les voix, le parfum du chiendent

sur la poussière acide

les grands balais de fibres réveillaient la pénombre

et c’était là la maison, là le temps

aucune vitre ne s’interposait entre nous et les choses.

c’était nous et l’aile des oiseaux,

nous et nous-mêmes

dedans, au sol, à la cave, la terre lévitait

humide et sèche

le bric-à-brac, malgré tous nos soins,

appartenait aux toiles d’araignées sans fin,

à la ferraille, aux pierres du pressoir

la lumière tombait.

c’était là l’enfance, là le temps.

je le jure, c’est encore

Extrait du livre Eutrapelia (2021)

.

CASA DOS AVÓS

dentro das tulhas caía o ar espesso da tarde,

a luz limpa e cálida de junho,

às vezes as vozes, o perfume do joio

sobre a poeira ácida

os vassourões acordavam a penumbra

e era aí a casa, aí o tempo

nenhum vidro se intrometida entre nós e as coisas.

éramos nós e a asa dos pássaros,

nós e nós mesmos

dentro, no chão, na cave, a terra levitava

húmida e seca

o bricabraque, por muito que o limpássemos,

pertencia às infindáveis teias de aranha,

à sucata, às pedras do lagar

a luz caía.

era aí a infância, era aí o tempo.

juro, ainda é

De Eutrapelia (2021)

.

•

PETIT ÉLOGE AUX CITRONS

à Céu

.

je les pèse dans la main, j’en caresse la peau ridée,

la poussière verdâtre reposant dans les volutes de leur

dos.

dans la corbeille, ils sont invariablement le soleil, lumière

que la maison chérit avec joie

le couteau qui les fend en deux se gorge de leur sang

translucide et parfumé – et amer –

et les narines s’emplissent de leur présence vive

et vigoureuse

aucun aliment ne méprise la sécrétion humble

de cet agrume, pas plus que la mémoire

ne dédaigne la voix des vieux maîtres que nous avons eus,

et qui autrefois

nous imposaient la décence inaltérable

du stylo sur le cahier

je dirais que le sang des citrons est candide

et peut-être un peu triste,

mais jamais inoffensif – jamais indifférent

(Poème inédit)

.

PEQUENO ELOGIO AOS LIMÕES

para a Céu

.

sopeso-os na mão, acaricio-lhes a pele enrugada,

o pó-verdete repousando entre as volutas do seu

dorso.

depois na fruteira eles são invariavelmente o sol, luz

que a casa acalenta com prazer

a faca que os corta pela metade enche-se do seu sangue

translúcido e perfumado – e amargo –

e as narinas ventilam a sua presença vívida

e pujante

nenhum alimento desdenha o segregar humilde

deste citrino, como não o faz a memória

à voz de velhos mestres que se tiveram, e que outrora

nos impunham a decência inquebrável

da caneta sobre o caderno

diria que o sangue dos limões é cândido

e talvez um pouco triste,

mas jamais inócuo – jamais indiferente

(Poema inédito)

.

•

LES GINKGO BILOBA D’HIROSHIMA

Pour Tsutomu Yamaguchi, ingénieur naval, le plus célèbre des hibakusha

Pour Akira Hasegawa, professeur, dont le corps et la maison disparurent dans l’air, comme poussière de papillon

.

après la terreur, il fallut nettoyer la ville.

les fonctionnaires impériaux venaient par roulements,

plongeaient les pelles dans les débris poudreux de la pierre,

balayaient la boue d’un côté à l’autre,

entendaient le vent gémir dans les cendres – le pire de tout

c’était ce sifflement du silence, ce crissement du fer sur les cadres sans verre,

dans les ruines des ponts qui dansaient comme des gonds,

dans les têtes qui mouraient plus lentement que les autres organes

les fonctionnaires de l’empire allaient

et venaient en roulements

parfois, ils enlevaient et pressaient leur casquette avec émotion,

conservaient dans de petits sarcophages de cèdre

les squelettes pas entièrement consumés par le grand embrasement

il fallut – il fallut – réapprendre

la carte de la pensée :

là, c’était le zoo, plus loin, l’école primaire,

cela – cette ombre calcinée sur le sol – une femme

avec un enfant dans les bras

parfois, on tombait à genoux à l’endroit précis

qui avait été la cachette purement intacte d’un rite,

d’un baiser, d’un adieu

jamais les mots ne parurent si peu nombreux parmi les décombres,

ni si amers,

ni si déments

des mois durant, se répétèrent le démantèlement, l’oubli,

la poursuite – le pire de tout,

c’était le noyau de la mort,

la manière dont elle ouvrait la gorge

et restait

Ichiro Kawamoto, à qui Philip Levine dédia

un poème puissant, affirma que, au printemps 46,

un miracle eut lieu :

vers la mi-mars, quelque vert détacha sa langue

dans le paysage infernal

– on regardait et voyait des bourgeons surgir des branches brisées

des ginkgos biloba,

renaissaient de petites pointes imprégnées de sève

et cela – pensaient les fonctionnaires de l’empereur –,

cela – pensons-nous – cela voulait dire quelque chose

21.03.2023

(Poème inédit)

.

AS GINGKO BILOBAS DE HIROSHIMA

Para Tsutomu Yamaguchi, engenheiro naval, o mais célebre dos hibakusha

Para Akira Hasegawa, professor, cujos corpo e casa desapareceram pelo ar, como pó de borboletas

.

depois do terror foi preciso limpar a cidade.

os funcionários imperiais vinham em turnos,

metiam as pás nos restos polvorentos da pedra,

varriam a lama de um lado para o outro,

ouviam o vento ganir nas cinzas – o pior de tudo era

este assobio do silêncio, esse guinchar do ferro nas aérolas sem vidro,

nos escombros das pontes que dançavam como dobradiças,

nas cabeças que morriam mais devagar do que os outros órgãos

os funcionários do império iam

e vinham em turnos

às vezes retiravam e apertavam o barrete cheios de comoção,

guardavam em pequenos sarcófagos de cedro

os esqueletos não inteiramente consumidos pelo grande lume

foi preciso – foi preciso – reaprender

o mapa do pensamento:

ali era o zoológico, acolá a escola primária,

aquilo – aquela sombra calcinada no pavimento – uma mulher

com o filho ao colo

às vezes caía-se de joelhos no lugar exato

que havia sido o esconderijo puramente intacto de um rito,

de um beijo, de uma despedida

nunca as palavras se pareceram tão poucas no entulho,

nem tão amargas,

nem tão dementadas

meses a fio repetiu-se o desmantelar, o esquecer,

o prosseguir – o pior de tudo era

o caroço da morte,

o modo como escancarava ela a garganta

e permanecia

Ichiro Kawamoto, a quem Philip Levine dedicou

um poema portentoso, afirmava que na primavera de 46 aconteceu

um milagre:

aí por meados de março, algum verde soltou a língua

na paisagem infernal

– olhávamos e víamos brotos sair dos ramos espedaçados

das gingko bilobas,

renasciam pequenas pontas impregnadas de seiva

e isto – pensavam os funcionários do imperador –,

isto – pensamos nós – isto queria dizer alguma coisa

21.03.2023

(poema inédito)

.

•

Biographie de l’auteur, sélection de textes et traduction par Emma Vousseur et Guillaume Meunier.

.